TEHRAN(Bazaar) –Ahmet T. Kuru, professor of political science at San Diego State University, says an independent class of economic entrepreneurs, which can be called bourgeoisie, is crucial for development.

In an interview with the Bazaar, Kuru also says, “In early Islamic history, there was such a class of merchants who made Muslim economies dynamic and funded independent scholars.”

He adds “Even today, the classes of economic entrepreneurs and intellectuals are very weak in the Muslim world.”

Following is the full text of the interview:

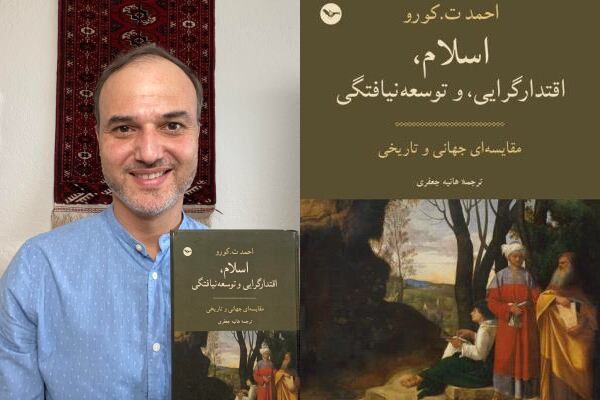

Bazaar: Your book, “Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Comparison” has been translated and published in Persian “اسلام، اقتدارگرایی و توسعهنیافتگی مقایسهای جهانی و تاریخی ”. What is the main argument of your book? What is the original contribution of your book in the analysis of underdevelopment in Islamic countries?

Kuru: My book was published by Cambridge University Press in 2019. It received the American Political Science Association’s International History and Politics book award. Recently, it has been translated into Arabic, Indonesian, and Persian. Its Persian translation has been published by Mehri Publications.

My book analyses 50 Muslim-majority countries. These countries show lower levels of democratization and socioeconomic development in comparison to the rest of the world. This is truly intriguing because between the eighth and eleventh centuries Muslim countries were scientifically, socially, and economically much more developed than Western Europe.

Many other books analyze this puzzle but they either blame Islam or Western colonialism as the sources of problems in the Muslim world. My book is different because it criticizes both of these two explanations. Islam was perfectly compatible with progress in its early history and continued to produce some eminent scholars even after the eleventh century. Western colonialism was detrimental but when it began to dominate the Muslim world in the eighteenth century, Muslims already had scientific and economic stagnation.

My book argues that the main cause of authoritarianism and underdevelopment in many Muslim-majority countries is the alliance between the ulema and the state. Between the eighth and eleventh centuries the independent scholars and the merchants were the engines of scientific and economic progress in the Muslim world. In the mid-eleventh century, however, the ulema and the state began to establish an alliance under the Seljuk Empire. Later, the ulema-state alliance was institutionalized under the Mamluks, Ottomans, and Safavids. In these empires and in many other countries, this alliance marginalized independent scholars and merchants, leading to centuries of intellectual and economic stagnation in the Muslim world.

Even today, the ulema-state alliance is still hindering socio-economic development and democratization in many contemporary Muslim countries by marginalizing independent scholars and merchants.

Bazaar: What was the importance of translating your book into Persian? What is the audience of this book?

Kuru: My book’s Persian translation is especially important because Iran has had a central position in the Muslim world from history to present. Iran produced many world-renown polymaths during Muslim’s “Golden Era” between the ninth and eleventh centuries. In this period, a reason for social and religious diversity was the existence of a certain degree of separation between the ulema and political rulers, which did not exist between the Catholic Church and kings in early medieval Europe. This ulema-state separation started with the Umayyad rulers’ persecution of Prophet Muhammad’s family members, including his grandson Hussein, and continued with the oppressive policies of certain Abbasid rulers. Hence, most Sunnis and Shiis regarded political authority as corrupt and contradicting morality. Both Sunni ulema, such as Abu Hanifa, Malik, Shafii, and Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and Shii ulema, such as Jafar al-Sadiq, refused to serve the state and put a distance between themselves and state authorities.

Nonetheless, in the mid-eleventh century there occurred a multi-dimensional transformation with economic, political, and religious aspects. The state structure became militarized and strengthened its control over the economy. A Sunni orthodoxy was formed as a joint construction of Arab Abbasids caliphs, Persian bureaucrats, and Seljuk Turks, who established an empire controlling Transoxiana, Iran, and Iraq. This Sunni orthodoxy was based on the newly emerging alliance between the ulema and the state.

The Seljuk model of ulema-state alliance was later spread to Syria and Egypt (under the Ayyubids and then Mamluks) and Anatolia and the Balkans (under the Ottomans). The Safavid rulers produced a Shii version of the model by establishing an alliance with Shii ulema.

Versions of the ulema-state alliance have continued until today as we see that in such modern states as Egypt, Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. Neither ulema nor political rulers are an economically productive class; therefore, they need a source of funding. Historically, the ulema-state alliance used agricultural revenues. Today, they mostly use oil rents, as seen in many Muslim-majority countries.

The audience of my book includes those who are interested in this historical and political analysis. Although my book is an academic work, its English, Arabic, and Indonesian versions have been read by many non-academic readers. I hope its Persian translation will also be read by a large audience without being limited to academic readers.

Bazaar: In your book, you have paid special attention to the creation of the “bourgeoisie” class in Islamic countries. You have also paid attention to the independent clergy and the intellectual class. Do we see the absence of the bourgeoisie in all the underdeveloped Islamic countries?

Kuru: An independent class of economic entrepreneurs, which can be called bourgeoisie, is crucial for development. In early Islamic history, there was such a class of merchants who made Muslim economies dynamic and funded independent scholars. These merchants innovated many financial tools, such as the check, originated from the Persian word sakk, are globally used today.

Nonetheless, after the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the ulema-state alliance began to marginalize independent merchants and scholars. Western Europe, however, experienced the opposite transformation. After the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Western Europe experienced the rise of city-states with a strong merchant class and the emergence of universities with a strong intellectual class.

Especially in the last three centuries, Western Europe surpassed the Muslim world, both economically and scientifically. This is a result of the presence of productive economic entrepreneurs and intellectuals in Europe and their absence in Muslim countries. Even today, the classes of economic entrepreneurs and intellectuals are very weak in the Muslim world.

Bazaar: One factor affecting development is “civil society”. Is the weakness of civil society in Islamic countries related to the weakness of bourgeoisie? Can it be said that the stronger civil society in a country, the more developed the country will be?

Kuru: Civil society means a set of associations which enable social interaction. It is different from political society (parties and other political groups) and economic society (corporations and other profit-oriented institutions). If civil associations are inclusive, then civil society promotes trust and toleration. In some cases, such as Germany between the two world wars, civil society was strong but exclusionary. Hence, it did not promote trust and toleration.

In order to see the flourishing of civil society, a country needs financially and intellectually independent individuals. That is why the weakness of civil society is associated with the lack of a strong bourgeoisie in many Muslim countries. I hope in the future Muslim countries will change and have independent merchants and intellectuals. This change will make civil society strong and that will help socio-economic development in these countries inshallah.

Bazaar: What is your book suggesting for the future of the Muslim world?

Kuru: With its comparative and historical analysis, my book proposes a new vision for the future of the Muslim world. My book does not recommend Muslims to simply embrace Western institutions and models. Instead, it stresses that if Muslims study their own early history, they will learn lessons of diversity, dynamism, and productivity. In their early history, Muslims were producing world-leading scientists and economic entrepreneurs. They can do that again in the future inshallah.

نظر شما